Artist Profile: Edris Hanifi A Creative Practice in Exile

Basic Space is pleased to present,

Edris Hanifi - A Creative Practice in Exile

Written by Ingrid Lyons

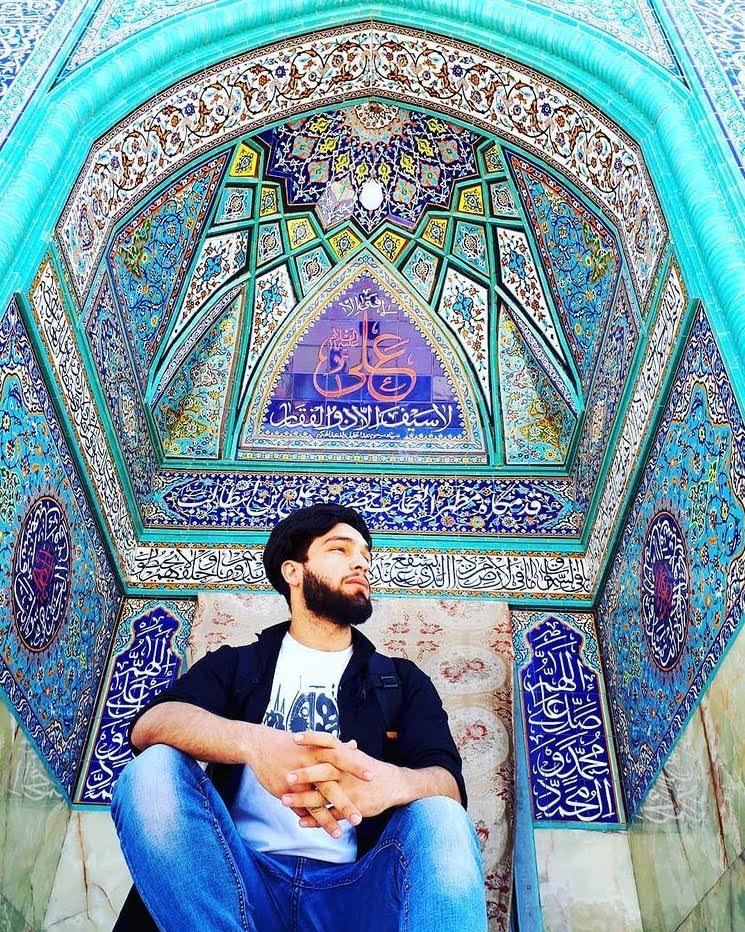

Edris Hanifi is an artist from Kabul, Afghanistan.

This presentation features works of art, created in adverse conditions after a sustained period of conflict. Hanifi’s art practice is focused on preserving the visual culture and intangible heritage of Afghanistan and he wishes to access manuscripts that will enable him to continue applied research in his specific field. This article hopes to introduce and support Hanifi's intention to visit and study manuscripts at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Edris Hanifi is from Kabul, Afghanistan, but his artistic focus has forced him into a life of exile in Iran, as making certain kinds of art is illegal under Taliban rule. Afghan Artists risk a lot to continue their practice and hone their craft , but continuing to practise is not a wilfully heroic stance for Hanifi who, like the rest of us, seeks to develop his art and make work in a safe environment.

Across a number of traditional skillsets and techniques, Hanifi’s work follows in the wake of the Herat school of traditional Miniature painting, where apprenticeship is a crucial component in creating a greater depth of understanding around the context and application of this medium in a contemporary setting. Hanifi views it as a crucial part of his practice, to observe details of techniques utilised by past masters like Ustad Kamaludin Behzad, for example, a painter and artist associated with the Tamiuri and Safavi periods. He also deeply admires teacher Qamarudin Chushti, a highly regarded calligrapher, and has studied under teachers Tamim Sahibzada and Hamida Ansari who taught him Miniature painting.

Due to political circumstances, original manuscripts from past masters cannot currently be accessed nor can Hanifi meet with mentors. As Hanifi seeks to rebuild his life after surviving a sustained period of war, he is faced with challenges of how to support himself and his family as an artist. His situation is also representative of the widespread issue of the loss of heritage in Afghanistan as links that support the passing-on of knowledge, technique, history and context are obliterated along with physical artworks.

‘Any artistic activity is currently being suppressed and I cannot paint whatever I like at will. I am also afraid of losing my life in any activity that I do. This is the biggest challenge and that is the reason why I am not in my country right now. Since the regime change, into the hands of the Taliban, I have not seen any kind of art activity. Eyes closed, mouths shut, ears deaf, this is the situation of all artists.’

Political circumstances have also complicated processes of preservation, as cultural movements become synonymous with clashing religious ideologies and objects of profound cultural significance are caught in the middle with artworks plundered, looted and destroyed. Countless artworks have succumbed to iconoclasm by the Taliban and many more lost to the black market and western art institutions where artefacts are stored indefinitely.

With Afghan artists disconnected from original manuscripts and the teachers of the skills and crafts needed to continue the tradition, Afghanistan suffers the erosion of visual identity. Rich cultural heritage bestows the philosophy of those who have created the art upon those who engage with it. Cultural expression is not a luxury or a leisure-time activity. The preservation of important cultural artefacts plays an active role in imprinting on contemporary cultural practices, which preserve collective memories and further a sense of belonging.

In the development of his own practice as an artist, illustrator, designer and calligrapher, Hanifi has focused on specific aspects of traditional Afghan cultural expression. His work incorporates three of the seven principal forms of calligraphy with a specialised focus on Kufic calligraphy.

‘I like Kufic calligraphy,’ Hanifi explains, ‘it’s also called the mother of calligraphy, and is the most recognisable and one of the oldest forms of Arabic calligraphy, developed between the 7th and 10th centuries and derived from the Iraqi town of Al-Kufa. It was a preferred script for writing the Qur’an and architectural decoration, and is still used by artists today. In the past, Kufic writing was often limited with colour codes but I began to challenge this. I first start writing the Qur’an verses in Kufic script, with natural pigments such as hammered Lapis, on my handmade paper.’

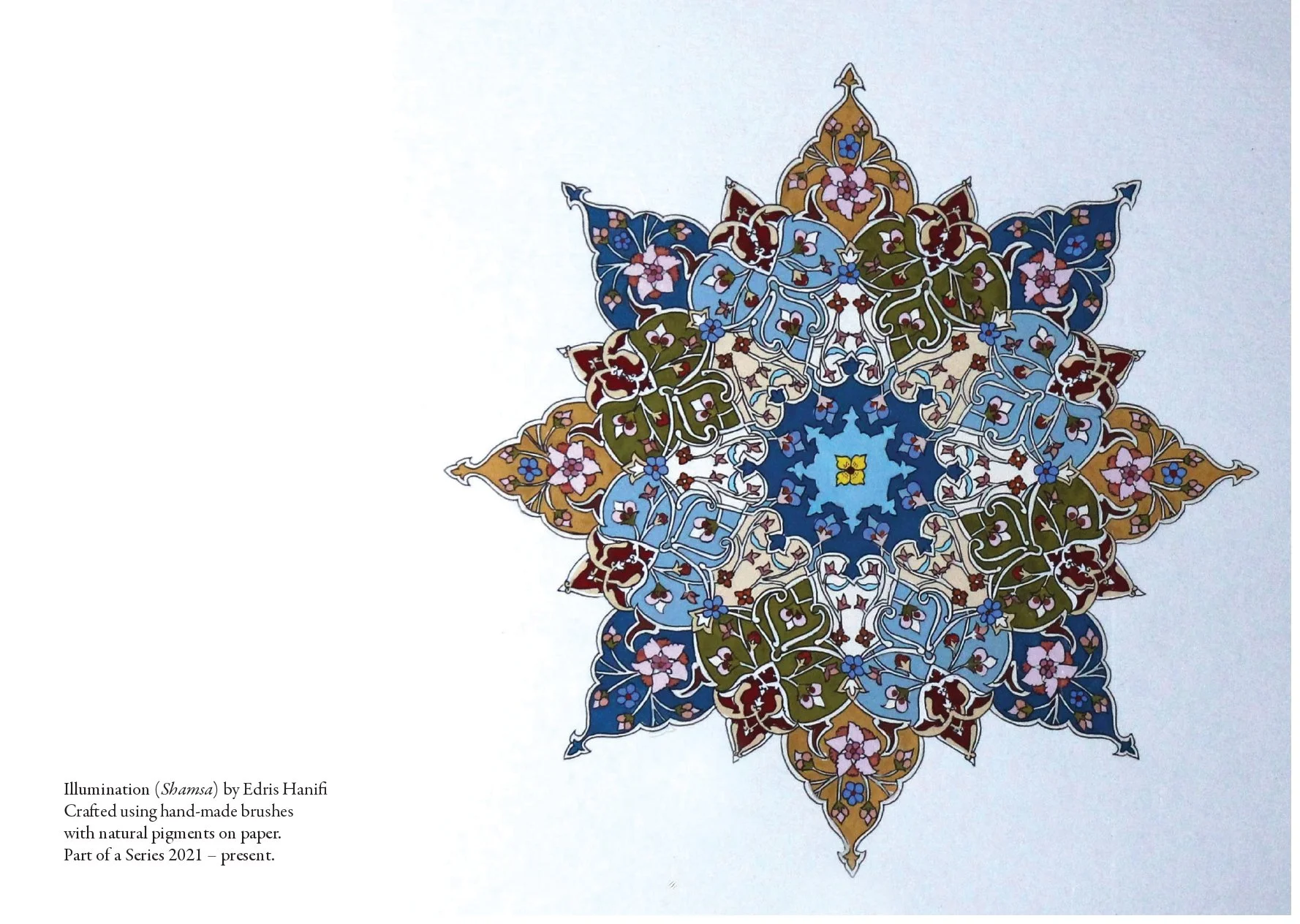

Teachers within the tradition extend specific skillsets to their student. Shamsa illuminations are often oval or circular in shape, and are frequently used as the frontispiece illuminations in Islamic manuscripts. They also stand alone, or as framing devices for calligraphic passages of Persian poetry. Hanifi’s artwork often directly refers to Shamsa illuminations.

Hanifi often embarks on the making of Shamsa within his practice.

‘Shamsa is taken from an Arabic word (Shams). Shams is the sun in Arabic and the small designs or small lines around the Shamsa is called Sharfa, again in Arabic. Sharfa is the sunburst, like rays of the Sun. Most of the time Shamsa are circular but, nowadays we are creating new designs with different shapes. In the past, when people wrote the Qur’an or wrote poetry, and even in the architecture of mosques, they always used Miniatures to make patterns around the writings to have a beautiful work of art. The kings of Islam developed the art of Miniature at the same time as the art of Calligraphy because they’re related to each other.’

Islamic geometric patterns are one of the significant forms of Islamic ornament, which tends to avoid using figurative images, as it is forbidden to create a representation of an important Islamic figure according to many holy scriptures. The geometric designs in Islamic art are often built on a combination of repeated squares and circles, which may be overlapped and interlaced. Within this specialised field, only artists who have developed an understanding of the craft are in a position to expand on the medium without threatening its integrity. The rules must be understood before they are broken. For example, Hanifi has developed skills that allow him to write and draw fluently and fluidly on silk with specially prepared pigments. He describes one such project with Turquoise Mountain, a non-governmental organisation that works to preserve cultural heritage in war torn and at risk communities. A group of artists and illustrators and craftspeople were commissioned to illuminate a copy of The Holy Qur’an which was made of silk. ‘This project took one year to complete, we were a group of 30 people I had an active part in that project, I was making the silk paper, mixing the colour, creating and referencing motif, developing patterns.’

In this environment, the artists were able to collaborate on each stage of the process. ‘For the first step, we cut the fabric a little bigger than A3 size, then tied the fabric to a wooden frame, and applied a mix of garlic sap with gum Arabic that was taken from the Acacia tree. We apply on it, once dried we cut the margins of silk paper, making it ready for writing or drawing. Finally, we wrote and created pattern all around the writing. I have to mention I also use a type of brush, which is made of cat hair. I just use it when I am doing gurative Miniature painting.’

The Chester Beatty Library in Dublin houses a rare manuscript from Afghanistan, composed by the poet Sa‘di in the thirteenth century. The Gulistan, meaning ‘Rose Garden’, is a series of flash fictions or anecdotes that focus on social issues. Vignettes of daily life are expanded on to unveil universal truths about the human condition. Within its pages, intricate motifs and rare patterns remember bygone golden eras of illustration and calligraphy. It is described as follows by its museum label:

‘The manuscript was produced for the Timurid prince Baysunghur, and the calligraphy is the work of the calligrapher Ja‘far, who was the head of Baysunghur’s atelier. In about AD 1430, Ja‘far wrote a report recounting the activities of the artists and craftsmen employed in the prince’s workshop. This copy of the Gulistan, which is thought to be one of the manuscripts mentioned in the report, is an exquisite example of the beautifully illustrated and illuminated manuscripts produced under the careful guidance of Baysunghur, who was himself a fine calligrapher.’

For Edris Hanifi, in this dedication to intricacy, complexity and detail, the emphasis within his practice is pinned to closely observing the materiality, texture, detail, nuance and structure of objects in situ. This is part of the training involved in the preservation of traditional skillsets. In the context of the cultural heritage of Afghanistan, Hanifi is a representative of an extremely small handful of people who are capable of learning, developing and passing on such an aptitude. And so, it has become an increasingly endangered artform as Hanifi himself is in physical danger. Such freehand skill and capability are essentially forms of intangible cultural heritage that can only be learned through applied research and apprenticeship. And the responsibility of an institution, perhaps, is to bring those with an artistic, embodied and spiritual understanding of such manuscripts into direct contact with them, to facilitate the observation and study of ancient philosophies of visual culture that they may be revived and preserved for future generations.

Last night I strutted about like a

peacock in the garden of union

But today, through separation from

my friend, I twist my head like a snake.

good if there were no fear of waves.

The company of the rose would be sweet if

there were no pain from thorns.

– Extract from The Gulistan of Sa’id (1427), from the manuscript in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin

Ingrid Lyons is an art writer and cultural commentator currently living and working in Donegal, Ireland.